Alex Constantine - January 1, 2014

Go ahead, use the search engine. America's public servants can't very well object to citizens spying on them if they have nothing to hide. Besides, President G.W. Bush made it abundantly clear that this country will not abide terrorism. As the Washington Post reported on August 25, 2010, “America has long been an exporter of terrorism, according to a secret CIA analysis released Wednesday by the Web site WikiLeaks. ..." Fight terrorism by using the search engine. Do your patriotic duty -- root out the terrorists operating at the highest levels of the US government. Nest week, I'll see if I can't scare up software for tapping their cell phones and laptops ... -- AC

Screenshot: "The Sphere of Influence" is an interactive visualization of State Department cables, mapping where government secrets travel around the globe and helping to flag anomalies.

On Google, you can find specialized tabs that only search all sorts of specific results, like news articles, images, patents, and scientific studies. The Declassification Engine is an ambitious project that aims to help citizens search for and uncover one very particular sort of result: U.S. government secrets.

The project, based out of Columbia University and launched about a year ago, uses advanced computer science methods in big data, machine learning, and natural language processing to scale up what some scholars have been struggling to do by hand for a decade: Document the rise of government secrecy, learn more about what the government isn’t releasing, and uncover new patterns and information in the millions of documents that do get declassified but contain heavy redactions.

Without more accountability, the historians, statisticians, computer scientists, and lawyers involved in the Declassification Engine project fear that our past will be “shredded in secrecy.”

“People have always complained about official secrecy, but over time there’s been measurable growth in the government secrets that are created,” says Columbia University historian Matthew Connelly, the co-leader of the project. “The whole system is breaking down.”

Today, to actually review the classified documents being created every year would demand the full-time work of every single federal and state government employee in the country, the project’s site says. The National Declassification Center has a current and rather hopeless backlog of 370 million pages of documents, and the government spends $10 billion protecting its secrets. It allocates only $50 million to declassification work.

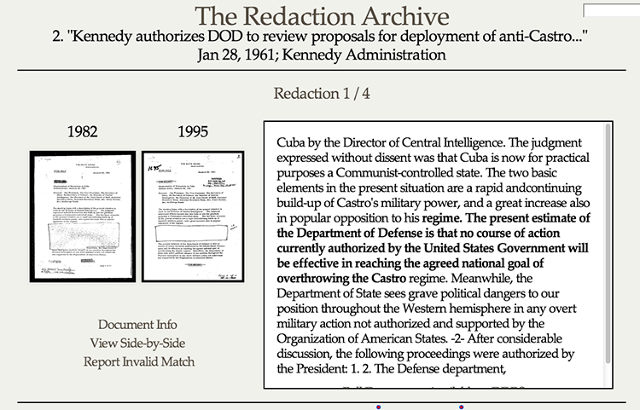

The Redaction Archive is another tool that is turning up matches of redacted and unredacted documents side-by-side to uncover what's beneath the black marker.

The Redaction Archive is another tool that is turning up matches of redacted and unredacted documents side-by-side to uncover what's beneath the black marker.The tools that the Declassification Engine have created thus far offer a glimpse into why the overabundance of secrecy hurts American democracy.

Their first mission was to gather as many declassified documents as possible into one database. The National Archives and other government troves are one source of information. But researchers have also collected others, such as scanned and full-text documents from private database companies like ProQuest and Gale Cengage Learning. Researchers involved in the project are now working with the Internet Archive to analyze the millions of PDFs that group has scraped from government sites since 1996. It also hopes to incorporate the results of FOIA requests, which are housed in online reading rooms of government agencies.

From this work, programmers and scientists are now starting to create apps, tools, and visualizations that will help others do analysis and searches.

Often, for example, the government posts declassified documents in different places and at different times--which means the redactions can differ. The Redaction Archive is turning up matches of redacted and unredacted documents side-by-side to uncover where they differ. This reveals the unknown text (like one sentence redacted from a 1969 memo from Henry Kissinger to Nixon which read: "In Israel, preasures [sic] will increase to deploy strategic missiles and nuclear weapons."), and it will also help academics to do large-scale pattern analysis of the "logic" of redaction. A “Redactometer” under development will measure the number of redactions in documents being released, to try to provide a degree of accountability to the process.

"The Sphere of Influence" is a massive visualization of the State Department’s early electronic diplomatic cables from 1973 to 1976 (the government hasn't yet released subsequent years). It seeks spatial patterns in the million declassified cables and also at the metadata, such as the “to” and “from” fields and certain topic words, from still-classified cables.

Secrets are the coin of the realm of government. It’s what people trade to get what they need.

One area of development is an accurate model that will try to predict which embassy a cable came from based on the language and topics used. “What’s interesting is the 2%--when it can’t accurately classify a cable. It means the cable is off-topic. What’s interesting about these off-topic cables is they tend to be classified a secret,” Connolly says. “Someone who is dealing with a million cables and they don’t even know where to begin--it’s a way to start.”

Already, there have been new insights from these tools. The research found that cables with the word “Boulder” in the subject or file name were 130 times more likely to be withheld from the public’s eye. Connolly found out this term referred to “Operation Boulder,” a little known program that existed in the 1970s that subjected Arabic visa applicants to an FBI investigation and that the Bush administration went to greater lengths to keep secret after 9/11. After learning about Operation Boulder through the Declassification Engine project, historians have delved in deeper and produced an exhibitabout the secret program.

The Declassification Engine project, which is really just getting started, aims to help both researchers, journalists, and citizens, but also hopes to help the government itself prioritize and speed-up its declassification backlog. An advisory board has been set up to make sure the "big data" processing proceeds with caution and doesn't tread too far into the realm of secrets that, for valid reasons, should be kept as such.

“Secrets are the coin of the realm of government. It’s what people trade to get what they need, whether that’s access or other information. Because there’s not a penalty to over classification, you get this built-in inflationary pressure where the currency of classification gets debased,” says Connelly. Releasing this pressure is clearly one motivation for the Bradley Mannings and Edward Snowdens of the world, he notes. But the Declassification Engine and other forms of more measured accountability could work, too.