Alex Constantine - April 5, 2023

By Ron Elving - NPR, July 22, 2021

In March of 2017, as clashes with the FBI director and attorney general were erupting just weeks into his presidency, Donald Trump was asking out loud: "Where's my Roy Cohn?"

In December of 2020, with just weeks left in his term, Trump still had not had his question answered.

He was surrounded by lawyers. But none could play the role — or take the place — of the controversial counselor who decades earlier had changed his life.

Cohn was already a legend when Trump met him in 1973. Cohn had been in the news for decades, prosecuting nuclear espionage or searching for communists or defending celebrity clients. Among those he represented were Cardinal Francis Spellman, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner and the New York crime bosses Carmine Galante and John Gotti.

Trump met him in the high-fashion Manhattan bar called Le Club and was soon relying on him for advice in dealing with lawsuits and legal orders and life in general. He drew up four versions of a prenuptial agreement prior to Trump's first marriage. (His first wife, Ivana Trump, died Thursday at 73.)

Cohn was known for telling clients to fight all charges, to counter-sue when sued and to never concede defeat. Trump has followed his formula for half a century, and that has come to matter a great deal to the nation.

While the former president has left office, he has not left the stage. He continues to trouble the political waters by denying he was defeated in 2020 and teasing a new candidacy for 2024. Moreover, he may yet face criminal charges for what he did in an attempt to stay in office after his defeat.

The committee closing in

This past week, the hearings of the House Select Committee to Investigate the Jan. 6 Attack on the Capitol took us back to the day that attack was set in motion.

It was Dec. 18, 2020, four days after the Electoral College had met in the 50 state capitols and elected Joe Biden the 46th president, obeying the results of the election as conducted in each state.

So even though his defeat was by then official, Trump was still trying to find some way to remain in power.

His efforts to overturn the 2020 results had made no headway in state or federal courts, even where the judges were Trump's own appointees. Law firms that had signed on to fight election fraud had found none and signed off. Trump could not even find a willing warrior within his White House legal team.

That's what led to the Dec. 18 meeting in the White House when two such lawyers – Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell – and other supporters talked to Trump about declaring martial law, using the military to seize voting machines or making Powell a "special counsel" with subpoena powers.

When White House Counsel Pat Cipollone heard that meeting was underway, he and others from his office intervened and objected strenuously. They said the moves under discussion lacked legal basis or justification, especially given the utter lack of evidence of fraud. There was no "steal" to stop.

But the outside team had another view.

"I would categorically describe it as: 'You guys aren't tough enough,'" reported Giuliani in videotaped testimony to the Jan. 6 committee.

Yet the brawl of the barristers continued, according to testimony, for six hours. It began in the Oval Office and continued upstairs in the personal residence. At one point, the committee was told, Trump gestured to his White House team and asked: "Do you see what I have to put up with?"

Trump was still looking for someone who would fight by another set of rules. All-in, no holds barred, no holding back. Someone for whom the only consideration was winning for the client. Someone like Roy Cohn.

A prodigy and a legend

Cohn was a prodigy, the son of a New York judge well acquainted with street politics as well as those of City Hall. Young Roy grew up immersed in both worlds. He would later be known for saying "Don't tell me what the law is, tell me who the judge is."

After rocketing through college and Columbia Law School, he was appointed an assistant U.S. attorney in New York at 20 (not old enough to vote at the time). Four years later he prosecuted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, accused of helping the Soviet Union access nuclear weapons secrets. Both went to the electric chair.

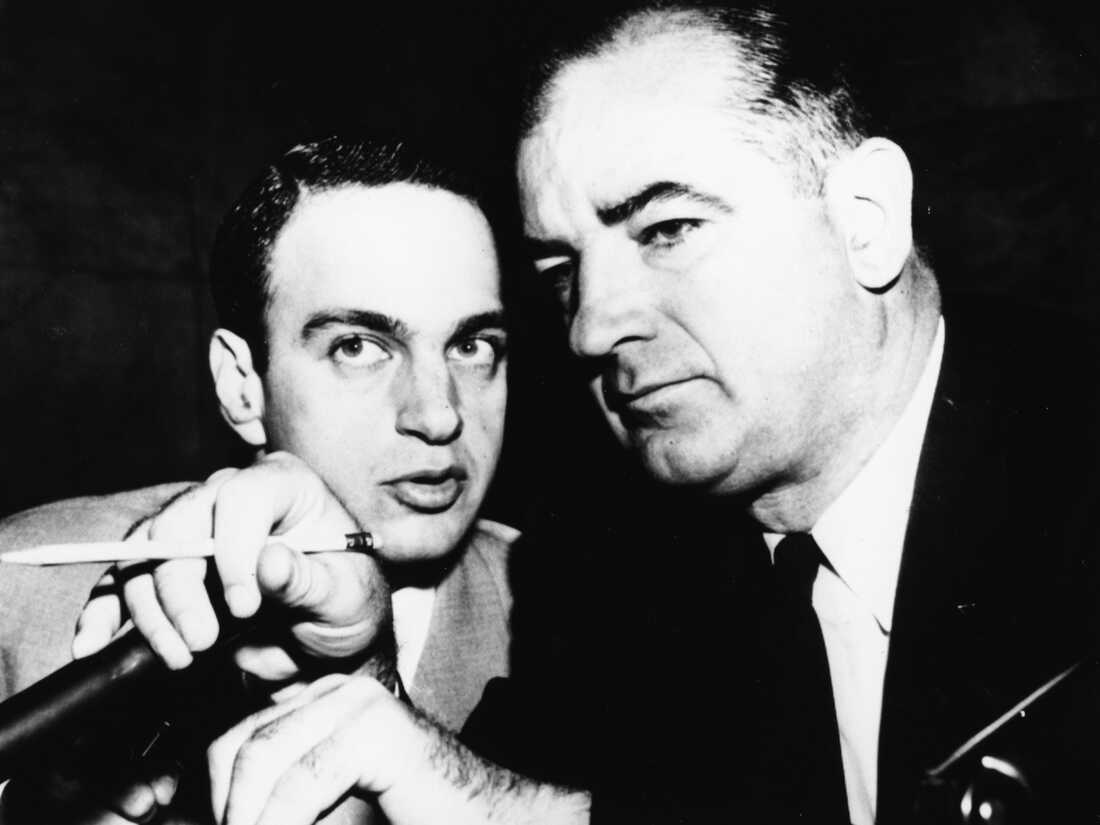

In the early 1950s, Cohn would be lead counsel for Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy when the first-term Republican from Wisconsin was chairman of a Senate committee looking for communists in government. Cohn was at his side as McCarthy was dominating the news and being mentioned for the Republicans' national ticket in 1952.

Although McCarthy never actually unmasked any actual communists, he destroyed many careers and lives. Along the way his name became synonymous with an era and with the tactic of making baseless but damaging accusations that did real damage despite being untrue.

Cohn was still with him when the senator took on the Army in 1954, claiming the Pentagon was protecting "reds" and Soviet sympathizers. That led to televised hearings that backfired and cost McCarthy much of his support in the GOP. McCarthy was censured by his colleagues in a highly unusual vote on the Senate floor. He left the chamber, never spoke there again and died a few years later.

Cohn, however, went back to New York and flourished. He had established a reputation for being tough to the point of being ruthless. And in the world of high-stakes lawsuits and prosecutions, that reputation was gold. And it was earned many times over.

Along the way, he met a young real estate developer on the move who would, improbably, turn out to be his most famous client of all.

A fateful meeting in a bar

She quotes Trump saying he brought up a racial discrimination lawsuit the U.S. Justice Department had filed against the real estate company he and his father ran. He asked Cohn if they should comply or try to compromise. Cohn shot back: "Tell them to go to hell and fight the thing in court and let them prove you discriminated."

The Trumps hired Cohn and soon announced they were suing the Justice Department for $100 million for "defamation." They later dropped that suit and stipulated to measures designed to prevent future discrimination at their properties. Running for president, Trump would respond to questions about all that by emphasizing there had been "no admission of guilt."

As successful as he was over his 40-year career, Cohn eventually ran afoul of the law himself. He was investigated by federal authorities for perjury and witness tampering, among other charges. In 1986, a panel of the New York State Supreme Court's Appellate Division disbarred him for unethical and unprofessional conduct. A short while later, Cohn died of complications of AIDS (although he always insisted in public that he was suffering from liver cancer).

What no client of Cohn's was ever left to wonder was whether or not Cohn was their champion. This may have been what shocked Trump most about being president. He expected the lawyers around him to be working for him, to be his champions. He discovered they saw their loyalty as being to their jobs, their oaths of office or the Constitution. Sometimes they agreed with him, sometimes they pushed back.

In his first weeks in office, Trump met with the FBI Director James Comey and asked repeatedly for a pledge of personal loyalty. Comey demurred and was soon fired. Trump had appointed Jeff Sessions, the Alabama Republican who had been his first supporter in the Senate, to be his attorney general. So he was stunned and enraged when Sessions recused himself from the investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Nearly four years later, after countless confrontations with the law and his own obligations to uphold it, Trump was still looking for a way around it. After the six-hour donnybrook of Dec. 18 had ended, and Chief of Staff Mark Meadows had personally escorted Giuliani out after midnight, Trump did not even wait for dawn to go on Twitter.