Alex Constantine - September 19, 2008

Also see: Corporate America and the Rise of Hitler

By Hans-Joachim Voth

www.resourceinvestor.com

18 Sep 2008

Around the globe, politically connected firms are more valuable. Nazi Germany was no different, though historians have lacked convincing evidence to prove that claim. This article shows that Nazi-linked firms reaped astoundingly large returns when Adolf Hitler came to power.

WASHINGTON, D.C. (voxEU.org) -- Few days defined the course of 20th century history as decisively as January 30th, 1933. With Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany, the course was set for another world war with millions of casualties, for genocide on an unprecedented scale, and for the abrupt end of Weimar’s vibrant cultural and intellectual life.

Who profited from the Nazi rise to power? Long before the first cabinet meeting was held under Chancellor Hitler, Communists had argued that the Nazi party was simply an instrument of capitalist forces. Memoirs of ambassadors and the investigations leading up to the Nuremberg trial seemed to confirm the complicity of many leading business men in the Nazi rise to power. This consensus was shattered a generation ago, when historians – Henry A. Turner (1985) most prominently among them – started to argue that there was no “smoking gun” linking big business and the Nazi party before 1933. Connections, he argued, had been isolated, were unrepresentative, and the total support given did not amount to much.

Instead of trawling the same overfished archives, Thomas Ferguson and I decided to look at what the financial markets saw when the Nazi party suddenly came to power (Ferguson and Voth 2005). Instead of having to assess the importance of every interaction between individuals, stock markets have the beauty that people have to put their money where their belief is. If the Nazi party’s rise to power made a big difference to the value of a firm that had given early support to the party, chances are that these contacts mattered.

Connected to the Nazis

Earlier academic work had focused mainly on the actions of managers. We broadened our definition of “connection”, by also analysing supervisory board members. Boards were particularly important in German public companies. Banks, for example, exercised power over affiliated companies through seats on supervisory boards. Any knowledgeable observer of the German corporate scene would have examined board composition to assess the political and economic positioning of a firm. An essential part of the work was to pin down supervisory board membership at the time of the takeover, which we did by analysing contemporary German sources.

In total, we found that 119 firms had connections with the Nazi party prior to January 1933. We counted leading businessmen as connected if they did one of three things:

Contributed funds to the Nazi party; Signed an appeal in the fall of 1932, directed to the German President Paul von Hindenburg, to make Hitler chancellor; and Contributed to two organisations designed to ’teach the Nazis economics’ – the Keppler Kreis and the Arbeitsstelle Schacht.

Financial support has long been regarded as the most important way in which big business aided the rise of the Nazi party. We go beyond this definition since an emerging consensus holds that membership contributions were the main source of party funding. While donating funds may have made a difference at critical junctures, it was probably not the most important form of support that Weimar’s business elite had to offer.

Hitler’s coming to office ultimately depended on the decision of the largely senile German President, Paul von Hindenburg. He personally loathed the “Bohemian corporal”. The conservative advisors around him were also sceptical about the Austrian firebrand. By organising an appeal to the President in the fall of 1932, when the Nazis had become the largest party in the German parliament, key players in the German business elite made Hitler a much more serious contender for power. Their backing lent an aura of respectability to “brown rabble”. By backing Hitler when and where it mattered most, German big business endorsed the radical movement’s suitability for office (Mommsen 2004).

Funding small policy units within the party worked in the same direction.

Prior to 1932, Nazi economic policy was largely dominated by cranks such as the party’s economist Gottfried Feder. His ideas included bills that would only keep their value if used constantly in transactions – to reduce incentives to keep “dead capital”. By raising the level of economic thinking in the Nazi party, businessmen made it a more serious contender for power.

Measuring performance

To measure performance, we collected the monthly stock price of 789 firms listed on the Berlin stock exchange. Prices were collected for the 10th of every month, from the day the exchanges opened again after the financial crisis of 1931 to May 1933.

We also collected information on the sector in which firms operated, the dividends they paid, their capital structure, and the overall market capitalisation. We defined 10 January 1933 as the last date before some investors may have suspected that the Nazi party might enter office. Some important meetings had already taken place by this date, but very few would have confidently predicted that on January 30th, Adolf Hitler would be German chancellor. As late as December 31st, many journalists who wrote “the year in review” columns had predicted that the Nazi wave had reached the high-water mark and would be receding.

How big was the Nazi premium?

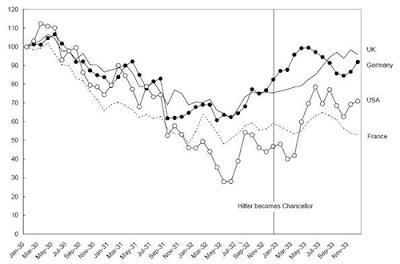

As Figure 1 shows, there is little to suggest that stock market investors as a whole cheered the Nazi rise to power to a significant extent. But the effects of the party’s ascent are evident in the cross-section of returns.

Figure 1 Stock market indices, 1930-1933

Figure 1 Stock market indices, 1930-1933

Firms connected with the Nazi party outperformed unaffiliated firms massively. Their share prices rose by 7.2% between January and March 1933 (43% annualised), compared to 0.2% (1.2% annualised) for unaffiliated firms. The politically induced change was equivalent to 5.8% of total market capitalisation. This is a high number by international standards. Johnson and Mitton (2003) estimate that revaluation of political connections in Malaysia during the East Asian crisis wiped 5.8% of share values. While comparable in magnitude, it took 12 months for this change to occur.

Affiliated firms did better, no matter their mode of connection with the party. The return differential favouring connected firms existed for both small and large firms, for firms in nine out of eleven sectors, and for those with high and low dividend yields. We also examined if expected rearmament was to blame for the value of connections, using lists of potential defence contractors compiled by the German armed forces (Hansen 1978). Our finding persists.

Why it paid

Around the globe, politically connected firms are more valuable (Faccio 2006). Nazi Germany was no different, but the sheer magnitude of the connection premium is astounding. Why did early connections with the party pay off as handsomely as they did? We do not know if loyalty was rewarded with additional contracts, loans on favourable terms, or in some other way such as privileged access to foreign exchange.

What is clear is that not enough firms sought to affiliate with the Nazis prior to January 1933 to drive the expected benefit – as seen by stock market investors – down to zero. This means that either many firms expected the benefits from association to be low (the Nazi party’s rise to power may have been a genuine surprise), or that they would not contemplate giving support for a variety of political reasons.

References

Faccio, Mara, “Politically Connected Firms,” American Economic Review, 96 (1) (2006), 369–386.

Ferguson, Thomas and Hans-Joachim Voth, “Betting on Hitler – The Value of Political Connections in Nazi Germany,” April 2005, CEPR Discussion Paper 5021.

Hansen, Ernst Willi, Reichswehr und Industrie: Rüstungswirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und wirtschaftliche Mobilmachungsvorbereitungen 1923–1932 (Boppard am Rhein: Boldt, 1978).

Johnson, Simon, and Todd Mitton, “Cronyism and Capital Controls: Evidence from Malaysia,” Journal of Financial Economics, 67 (2) (2003), 351–382.

Mommsen, Hans, Aufstieg und Untergang der Republik von Weimar, 2nd ed. (Munich: Ullstein Heyne, 2004).

Turner, Henry A., German Big Business and the Rise of Hitler (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1985).

http://www.resourceinvestor.com/pebble.asp?relid=46278